Debugging, Profiling, and a Bit of Optimization

RaukR 2024 • Advanced R for Bioinformatics

Marcin Kierczak

21-Jun-2024

Run Forrest, run!

- My code does not run! – debugging

- Now it does run but… out of memory! – profiling

- It runs! It says it will finish in 5

minutesyears. – optimization

Types of bugs

- 🔣 Syntax errors

- 🧩 Logic

Everything works and produces seemingly valid output that is WRONG!

IMHO those are the hardest 💀 to debug!

How to avoid bugs

- Encapsulate your code in smaller units 🍱 (functions), you can test.

- Use classes and type checking 🆗.

- Test 🧪 at the boundaries, e.g. loops at min and max value.

- Feed your functions with test data 💾 that should result with a known output.

- Use antibugging 🕸:

stopifnot(y <= 75)

Floating confusion

[1] 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9

[1] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[1] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE[1] 0

[1] -1.110223e-16💀 Beware of floating point arithmetic! 💀

How to float 🏊

Comparing floating point numbers:

Final thoughts on floating

double.eps double.neg.eps double.xmin double.xmax double.base

2.220446e-16 1.110223e-16 2.225074e-308 1.797693e+308 2.000000e+00

double.digits

5.300000e+01 Handling Errors

Let us generate some errors:

input <- c(1, 10, -7, -2/5, 0, 'char', 100, pi, NaN)

for (val in input) {

(paste0('Log of ', val, 'is ', log10(val)))

}Error in log10(val): non-numeric argument to mathematical function

So, how to handle this mess?

Handling Errors – try

[1] "Log of 1 is 0"

[2] "Log of 10 is 1"

[3] "Log of -7 is NaN"

[4] "Log of -0.4 is NaN"

[5] "Log of 0 is -Inf"

[6] "Log of char is NA"

[7] "Log of 100 is 2"

[8] "Log of 3.14159265358979 is 0.497149872694133"

[9] "Log of NaN is NaN" Handling Errors – tryCatch block:

[1] "Log of 1 is 0"

[1] "Log of 10 is 1"

[1] "Warning! Negative argument supplied. Negating."

[1] "Log of -7 is 0.845098040014257"

[1] "Warning! Negative argument supplied. Negating."

[1] "Log of -0.4 is -0.397940008672038"

[1] "Log of 0 is -Inf"

[1] "Log of NA is NA"

[1] "Log of 100 is 2"

[1] "Log of 3.14159265358979 is 0.497149872694133"

[1] "Log of NaN is NaN"Debugging – errors and warnings

- An error in your code will result in a call to the

stop()function that:- Breaks the execution of the program (loop, if-statement, etc.)

- Performs the action defined by the global parameter

error.

- A warning just prints out the warning message (or reports it in another way)

Debugging – what are my options?

- Old-school debugging: a lot of

printstatements- print values of your variables at some checkpoints,

- sometimes fine but often laborious,

- need to remove/comment out manually after debugging.

- Dumping frames

- on error, R state will be saved to a file,

- file can be read into debugger,

- values of all variables can be checked,

- can debug on another machine, e.g. send dump to your colleague!

- Traceback

- a list of the recent function calls with values of their parameters

- Step-by-step debugging

- execute code line by line within the debugger

Option 1: dumping frames

Hint: Last empty line brings you back to the environments menu.

Option 2: traceback

Error in log10(x): non-numeric argument to mathematical function> traceback()

2: f(x) at #2

1: g("test")traceback() shows what were the function calls and what parameters were passed to them when the error occurred.

Option 3: step-by-step debugging

Profiling – proc.time()

Profiling is the process of identifying memory and time bottlenecks 🍾 in your code.

user time– CPU time charged for the execution of user instructions of the calling process,system time– CPU time charged for execution by the system on behalf of the calling process,elapsed time– total CPU time elapsed for the currently running R process.

Profiling – system.time()

user system elapsed

0.260 0.009 0.268

user system elapsed

0.433 0.020 0.454 Profiling in action

These 4 functions fill a large vector with values supplied by function f.

1 – loop without memory allocation.

Profiling in action cted.

But it is maybe better to use…

vectorization!

3 – vectorized loop without memory allocation.

Profiling our functions

| fn | user.self | sys.self | elapsed |

|---|---|---|---|

| fn1 | 11.973 | 0.099 | 12.073 |

| fn2 | 0.386 | 0.032 | 0.418 |

| fn3 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.002 |

| fn4 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.002 |

The system.time() function is not the most accurate though. During the lab, we will experiment with package microbenchmark.

More advanced profiling

We can also do a bit more advanced profiling, including the memory profiling, using, e.g. Rprof() function.

And let us summarise:

| self.time | self.pct | total.time | total.pct | mem.total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “runif” | 2.13 | 48.41 | 2.13 | 48.41 | 1899.0 |

| “eval” | 1.04 | 23.64 | 3.29 | 74.77 | 3334.7 |

| “print.default” | 0.85 | 19.32 | 0.85 | 19.32 | 72.1 |

| “fun_fill_loop2” | 0.24 | 5.45 | 3.53 | 80.23 | 3646.3 |

| “parent.frame” | 0.06 | 1.36 | 0.06 | 1.36 | 64.6 |

| “is.list” | 0.05 | 1.14 | 0.05 | 1.14 | 82.3 |

| “is.pairlist” | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 23.1 |

| “mayCallBrowser” | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 1.0 |

| “strsplit” | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.4 |

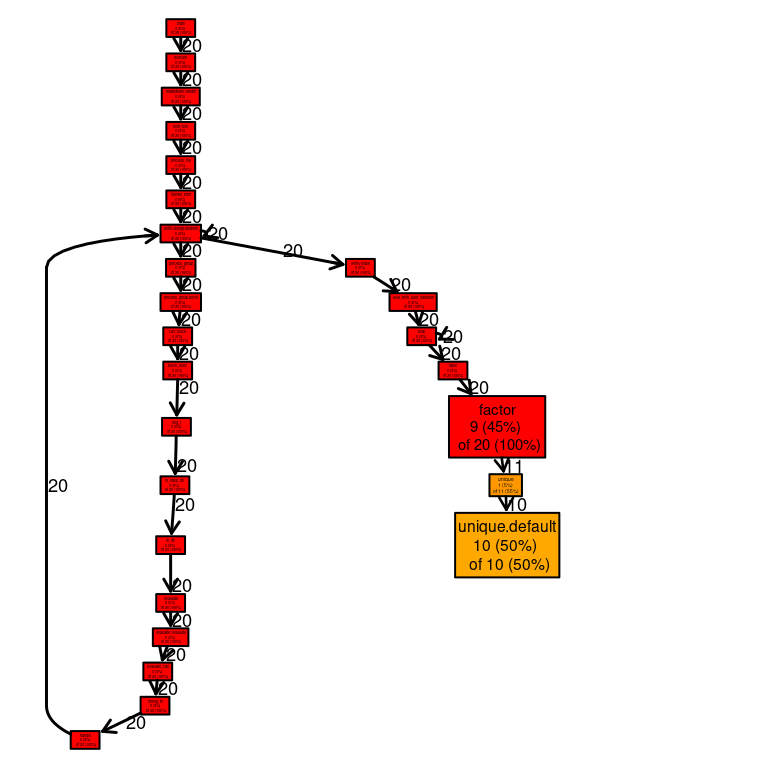

Profiling – profr package

There are also packages available that enable even more advanced profiling:

This returns a table that can be visualised:

| level | g_id | t_id | f | start | end | n | leaf | time | source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | .main | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | NA |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | execute | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | NA |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | rmarkdown::render | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | NA |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | knitr::knit | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | NA |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | process_file | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | NA |

| 6 | 1 | 1 | handle_error | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | NA |

| 7 | 1 | 1 | withCallingHandlers | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | base |

| 8 | 1 | 1 | withCallingHandlers | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | base |

| 9 | 1 | 1 | process_group | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | NA |

| 10 | 1 | 1 | process_group.block | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | NA |

| 11 | 1 | 1 | call_block | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | NA |

| 12 | 1 | 1 | block_exec | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | NA |

| 13 | 1 | 1 | eng_r | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | NA |

| 14 | 1 | 1 | in_input_dir | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | NA |

| 15 | 1 | 1 | in_dir | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | NA |

| 16 | 1 | 1 | evaluate | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | NA |

| 17 | 1 | 1 | evaluate::evaluate | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | NA |

| 18 | 1 | 1 | evaluate_call | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | NA |

| 19 | 1 | 1 | timing_fn | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | NA |

| 20 | 1 | 1 | handle | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | NA |

| 21 | 1 | 1 | withCallingHandlers | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | base |

| 22 | 1 | 1 | withVisible | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | base |

| 23 | 1 | 1 | eval_with_user_handlers | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | NA |

| 24 | 1 | 1 | eval | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | base |

| 25 | 1 | 1 | eval | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | base |

| 26 | 1 | 1 | table | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | base |

| 27 | 1 | 1 | factor | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1 | FALSE | 0.40 | base |

| 28 | 1 | 1 | unique | 0.00 | 0.22 | 1 | TRUE | 0.22 | base |

| 29 | 1 | 1 | unique.default | 0.02 | 0.22 | 1 | TRUE | 0.20 | base |

Profiling – profr package cted.

We can also plot the results using – proftools package-

Profiling with profvis

Yet another nice way to profile your code is by using Hadley Wickham’s profvis package:

Profiling with profvis cted.

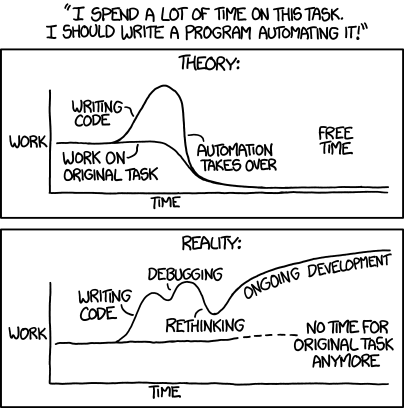

Optimizing your code

We should forget about small efficiencies, say about 97% of the time: premature optimization is the root of all evil. Yet we should not pass up our opportunities in that critical 3%. A good programmer will not be deluded into complacency by such reasoning, he will be wise to look carefully at the critical code; but only after that code has been identified.

– Donald Knuth

source: http://www.xkcd/com/1319

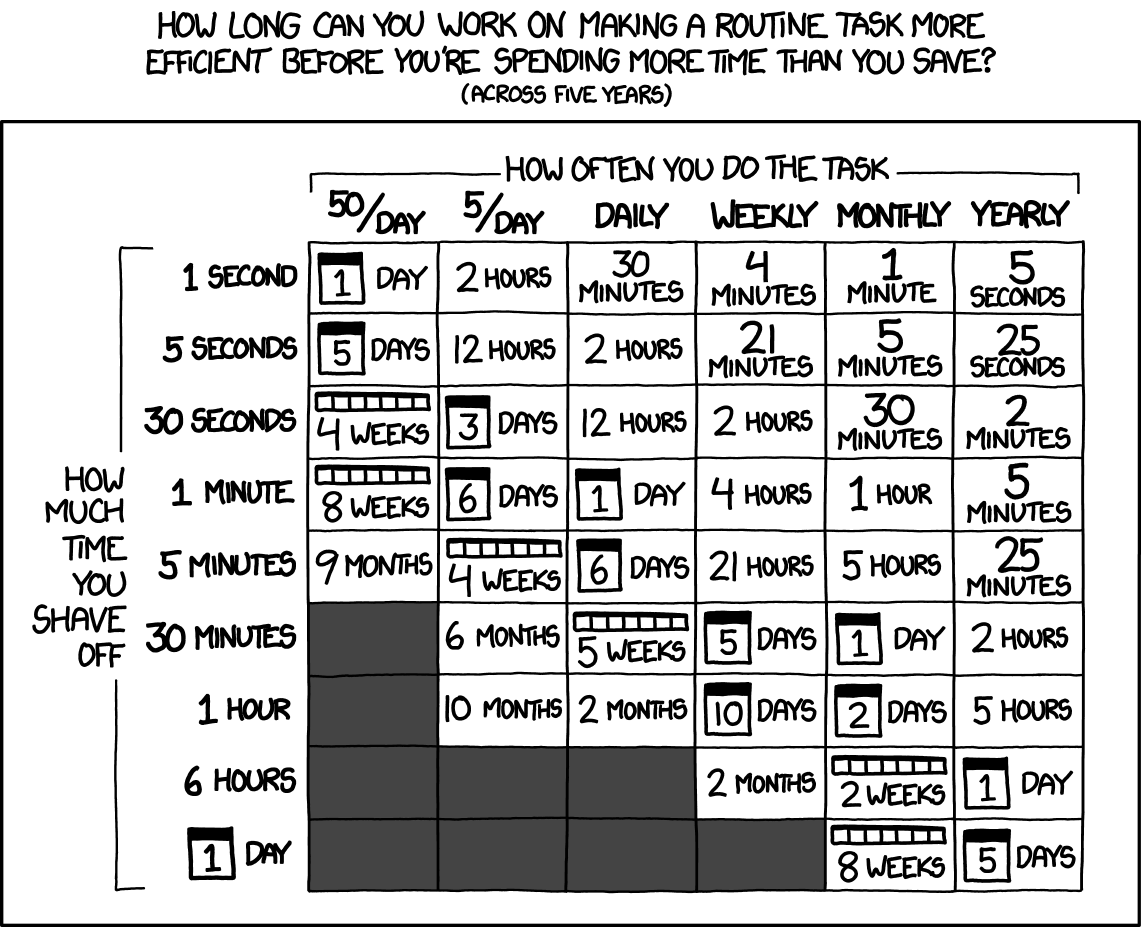

source: http://www.xkcd/com/1205

Ways to optimize the code

- write it in a more efficient way, e.g. use vectorization or

*applyfamily instead of loops etc., - allocating memory to avoid copy-on-modify,

- use package

BLASfor linear algebra, - use

bigmemorypackage, - GPU computations,

- multicore support, e.g.

multicore,snow - use

futures - use

data.tableortibbleinstead ofdata.frame

Copy-on-modify

Check where the objects are in the memory:

What happens if we modify a value in one of the matrices?

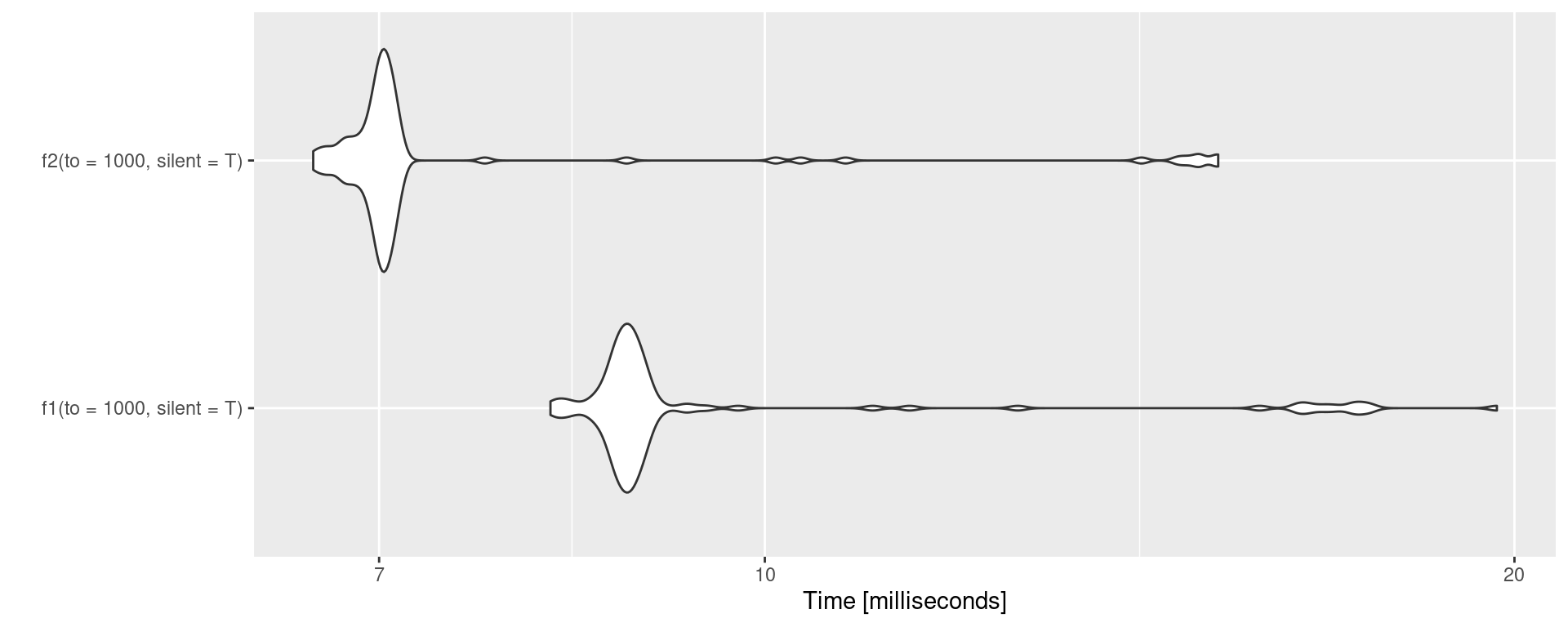

Avoid copying by allocating memory

No memory allocation

Avoid copying by allocating memory cted.

With memory allocation

f2 <- function(to = 3, silent = FALSE) {

tmp <- vector(length = to, mode='numeric')

for (i in 1:to) {

a1 <- address(tmp)

tmp[i] <- i

a2 <- address(tmp)

if(!silent) { print(paste0(a1, " --> ", a2)) }

}

}

f2()[1] "0x561ca87f50d8 --> 0x561ca87f50d8"

[1] "0x561ca87f50d8 --> 0x561ca87f50d8"

[1] "0x561ca87f50d8 --> 0x561ca87f50d8"Allocating memory – benchmark.

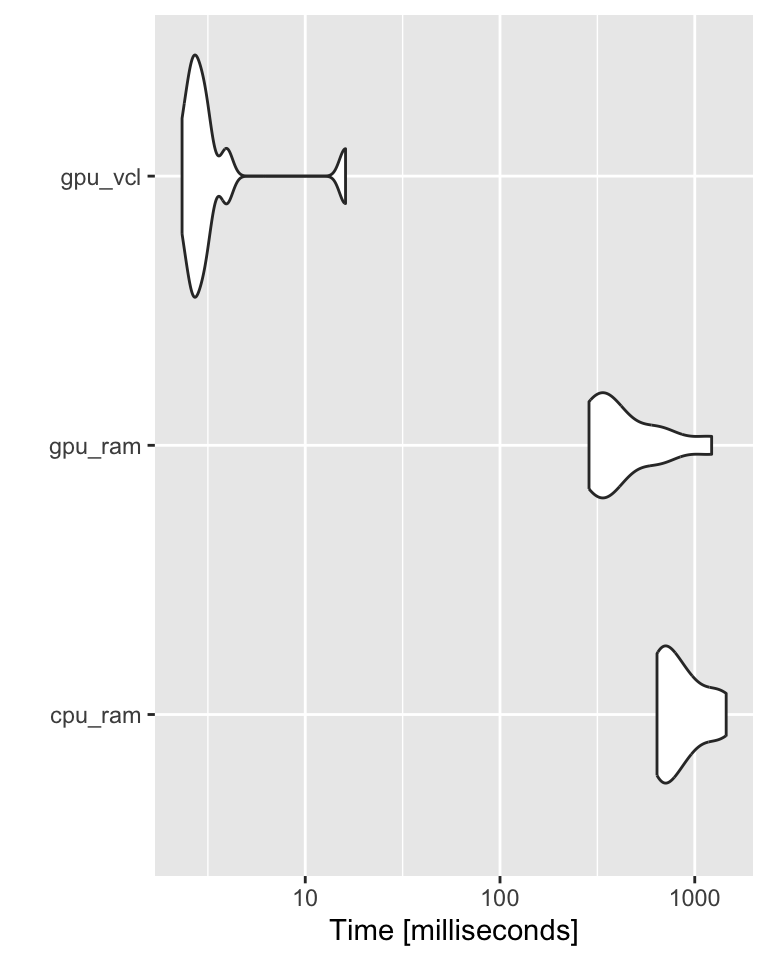

GPU

A = matrix(rnorm(1000^2), nrow=1000) # stored: RAM, computed: CPU

B = matrix(rnorm(1000^2), nrow=1000)

gpuA = gpuMatrix(A, type = "float") # stored: RAM, computed: GPU

gpuB = gpuMatrix(B, type = "float")

vclA = vclMatrix(A, type = "float") # stored: GPU, computed: GPU

vclB = vclMatrix(B, type = "float")

bch <- microbenchmark(

cpu_ram = A %*% B,

gpu_ram = gpuA %*% gpuB,

gpu_vcl = vclA %*% vclB,

times = 10L) More on Charles Determan’s Blog.

GPU cted.

Parallelization using package parallel

Easiest to parallelize is lapply:

Thank you! Questions?

_

platform x86_64-pc-linux-gnu

os linux-gnu

major 4

minor 3.2 2024 • SciLifeLab • NBIS • RaukR