Principal component analysis

Clustering and dimensionality reduction

PCA in population genetics

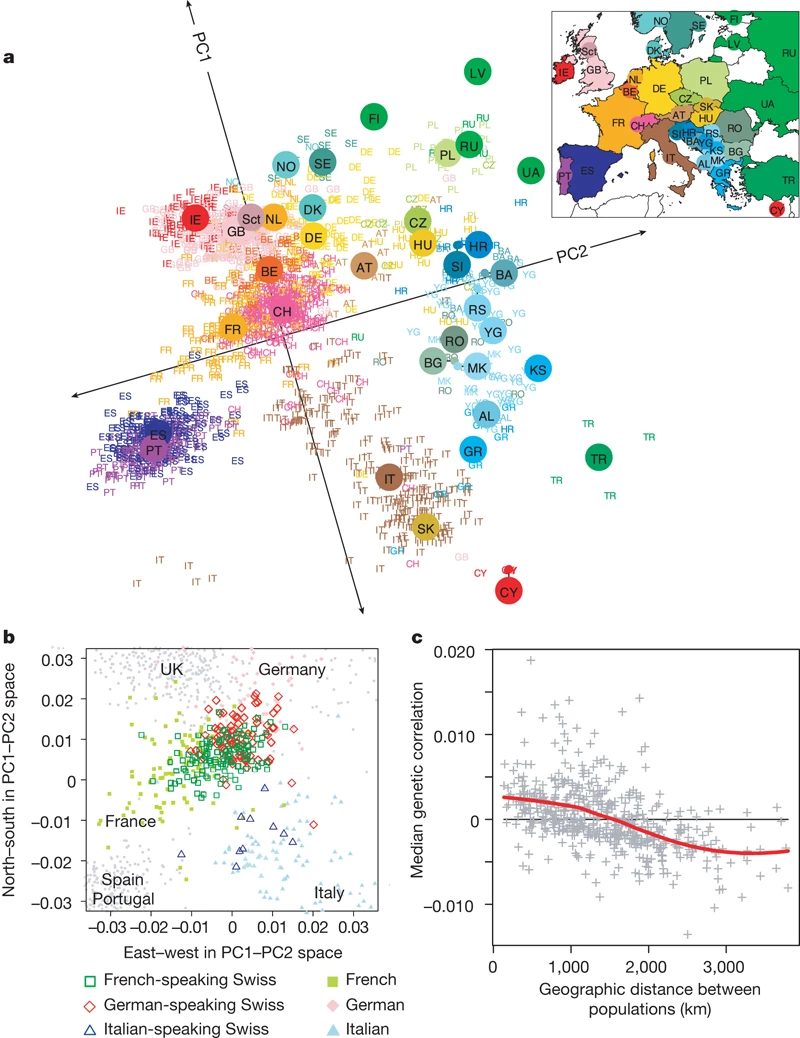

Beware: Novembre & Stephens (2008) pointed out that patterns may be due to mathematical artifacts and not necessarily directly inform us about the underlying demographic process!

PCA in population genetics

PCA is a matrix factorization technique

An entry in the genotype matrix is approximated by the K first loadings

G_{ij} \approx \mathbf{\Lambda}_i \mathbf{F}_j

Toy example of PCA for population genetics

gen <- t(matrix(c(1, 0, 2, 0, 2, 0, 2, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 2, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1,

0, 1, 0, 2, 0, 1, 1, 0, 2, 1, 2, 0, 1, 0), 5, by = TRUE))

colnames(gen) <- paste0("Ind", 1:5)

rownames(gen) <- paste0("SNP", 1:7)

print(gen) Ind1 Ind2 Ind3 Ind4 Ind5

SNP1 1 1 1 0 0

SNP2 0 1 2 1 2

SNP3 2 1 1 0 1

SNP4 0 0 1 2 2

SNP5 2 1 1 0 0

SNP6 0 0 1 1 1

SNP7 2 2 1 1 0Idea: project the data into a low dimensional space that explains the largest amount of variance

Geometric interpretation

Example of PCA plot of Monkeyflower data

We will use plink2 (Chang et al., 2015) to generate PCA plots.

LD pruning

PCA assumes independent markers!

PCA

Construct PCA from subset of pruned markers

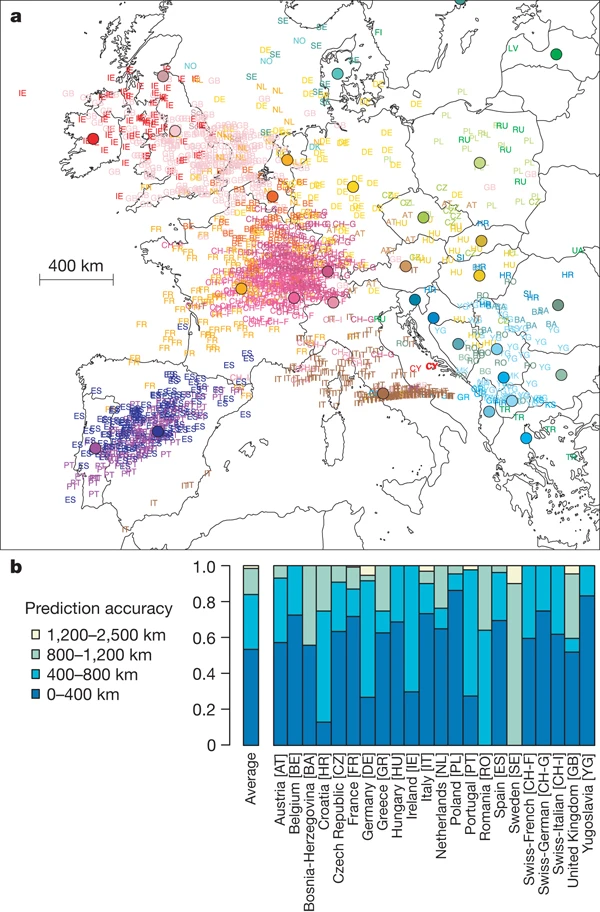

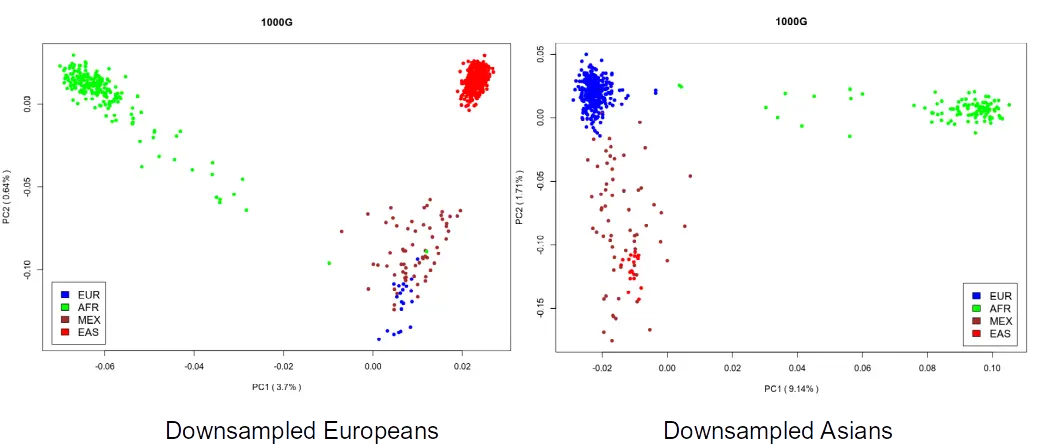

Uneven sampling may distort PCA projections

“The results described here provide an explanation. First, from Equation 10 it can be seen that the matrix M is influenced by the relative sample size from each population through the components t_i. For instance, even if all populations are equally divergent from each other, those for which there are fewer samples will have larger values of t_i because relatively more pairwise comparisons are between populations.”

M=XX^T=\frac{1}{N}\sum_{ij}x_ix_j N=N_{pop1}+N_{pop2}+N_{pop3}+...=\sum_k N_k M_{uneven}=\sum_{ijk}\frac{1}{N_k}x_{ik}x_{jk}

- Potential solution: normalize each sample by its population size before computing the covariance matrix.

- Is it still an unsupervised technique?

Example of uneven sampling

Bibliography

Population Genomics in Practice