Overview

Teaching: 15 min

Exercises: 15 minQuestions

Why and how do we keep good research records?

How do we keep our records FAIR?

Objectives

Identify the pros and cons of analogue vs. digital notes

Adopt good practices for data analysis documentation

About this episode

The data you collect, organise, prepare, and analyse to answer your research questions and the documentation describing it are the lifeblood of your research. Put bluntly: Without data, there is no research. And while data is important, without proper documentation, your data may be useless for both yourself and others in the future.

Starting up Your Research

Congratulations researcher! You have been recruited to the lab of Professor Terry Williams (often called “Terry”), a well-established authority in the field with many benchmark publications to his name. It is truly an honour to work here, and you outcompeted several applicants to earn the position. It will be a major addition to your CV and will likely increase your chances of receiving funding for your own projects in the future.

The road to success is open!

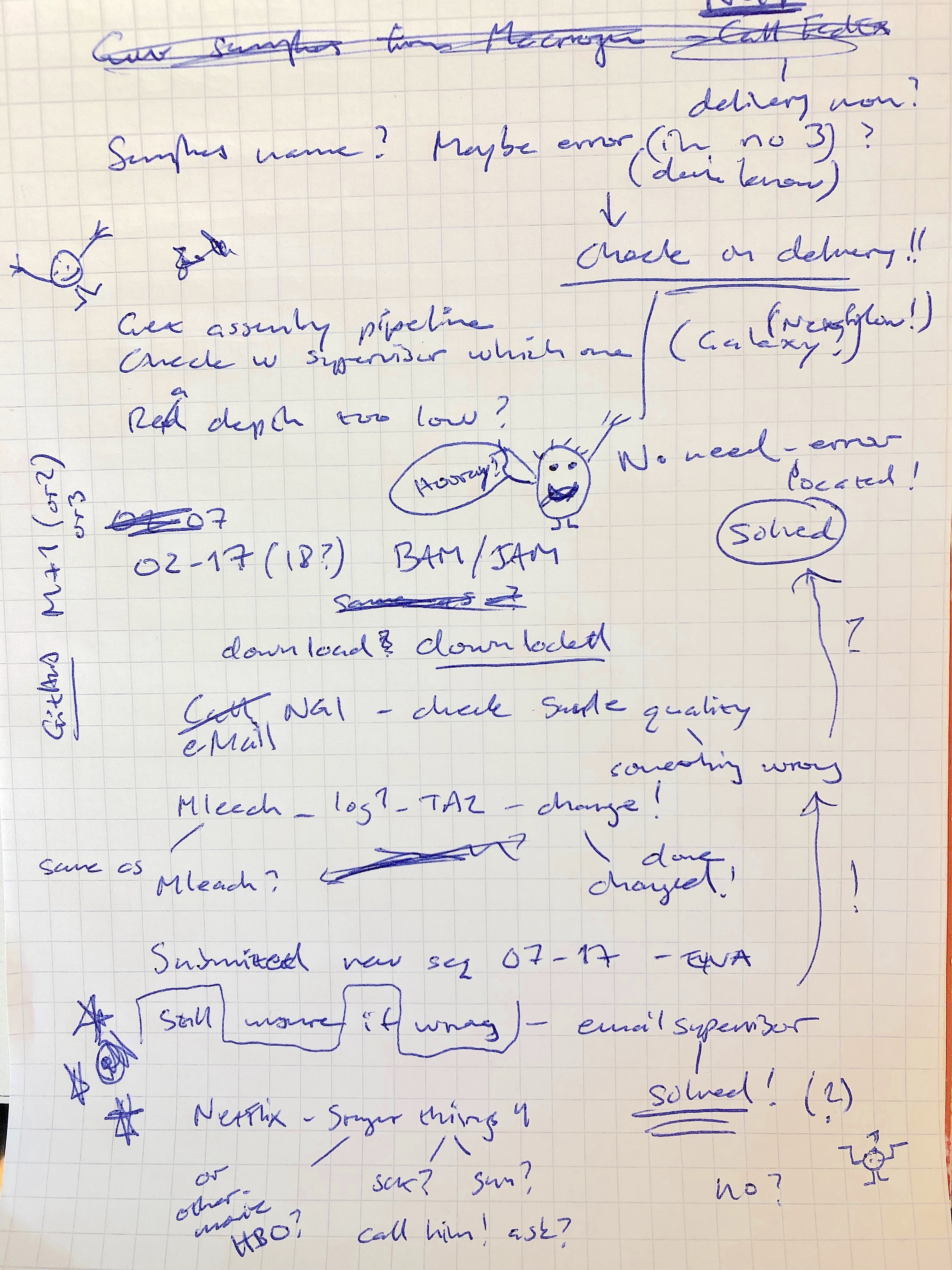

On your first day of work, Terry informs you that you will continue and build on the work left behind by a previous PhD student, Emily Johnson, who left the lab six months ago to pursue a career elsewhere. Former coworkers say she could be working in the industry, at another university, or possibly abroad — nobody knows for sure. Before leaving, Emily sent Terry a photo of her lab notes, which document the data you will work with.

She also left behind a USB stick containing all known files and folders in a zip file.

Puzzled by the note, you ask Terry for additional information. The reply is that all researchers in the lab work independently and are responsible for their own data and lab notes. If the information is not in the notes, the publication, or the zipped folder, it does not exist.

Exercise 1

Can you list at least five major issues with the lab documentation in the image above?

Examples of major issues

- Unknown if more pages of the notes exist

- Difficult to read the text

- Not all text is included in the image

- Explicit dates are lacking

- Text follows no clear structure

- Notes follow no clear timeline

- Notes mixed with scribbles

- Unknown if errors in data and/or file names are/were corrected or not

- Unknown how notes relate to data

- Changes to files are not referenced in the zip file

- Notes indicate more information exists (email to supervisor)

- Notes raise questions about data quality

- Lab notes are mixed with personal notes

- Unknown what analysis pipeline was used

- Etc…

Exercise 2

Give one or more example(s) of what kind of general questions the note and Terry’s answer raise about the work done in the lab.

Problem areas

- Is this typical of all the work done in the lab?

- What results from the lab can be trusted?

- Are there no established routines for data documentation?

- Are there no established routines for data backup?

- Etc…

We will come back to work at the lab later. What we need to ask ourselves now is…

Why do we need to keep good-quality records?

Good scientific practice relies on maintaining accurate and thorough records. Good records ensure that the data, analysis, and results are transparent, reproducible, and traceable to relevant individuals. Traceability also ensures that someone is accountable and can be contacted for further questions and clarifications.

Keeping good records will prevent future issues, where revelations about the past data handling and metadata quality can question not only the original results but also the subsequent research building on such data; (A recent example). As science is cumulative, uncorrected mistakes may multiply over time.

Good practice reduces the risk of data mistakes, data manipulation and research fraud. Making data and documentation open and transparent promotes the values of open science and, in the long term, safeguards the integrity of science itself. The inability to share data and documentation, as well as inconsistencies in published results, have revealed high-level fraud in the realm of science (e.g. the infamous cases of Dr. Yoshitaka Fuji, or Joachim Boldt), who both fabricated data and results, resulting in hundreds of retracted papers.

Not only is the fabrication of data and/or results a threat to the integrity of science itself. Once published, fraudulent papers can keep on being cited years after being retracted.

While fraudulent activity is indeed a problem, the more positive arguments for maintaining good-quality records can be described by the FAIR principles. Good records promote data and documentation being

- Findable,

- Accessible,

- Interoperable, and

- Reusable

In that context, written lab notes on paper can still fulfil the FAIR principles, but to a lesser degree than digital ones. Making your lab notes and protocols digital and even available online promotes sharing them with anyone who needs them for publication. Submitting them to a public repository (e.g. Zenodo or FigShare) provides them with persistent identifiers (PIDs) and makes them readily citable.

There are several platforms for keeping digital lab notes (see here for a comprehensive list and comparison of different platforms), documenting your workflow and making the data and documentation easier to access and share among people and across time.

Note

Records, data, metadata, and documentation are closely related but not identical:

- Data: The actual measurements, observations, or files generated (e.g. images, sequences, tables).

- Metadata: Data about the data (e.g. sample ID, instrument, date, settings).

- Documentation: Text explaining how the data were generated and processed.

- Records: The entire collection of data, metadata, notes, protocols, and decisions.

Good record-keeping ensures that all four remain connected and interpretable over time.

Principles for good records

Protocols and lab notes should be kept detailed, up-to-date, and accurate. They should be accessible and easily understood by both you and others, regardless of when. Keeping records in digital format ensures easy backup and increased shareability. Content of records can include, but should not be limited to:

- Your name, affiliation and contact information

- Who the originator of the protocol is (if not you)

- Detailed and structured information on why and how an experiment was done

- Health and safety advice

- Required hardware, software, or materials/instruments being used and when/where they were obtained

- Sufficient information so that someone can understand what has been done without having to ask others

- Described mistakes so they can be avoided in future applications of the protocol

While the protocol is a confirmed recipe for generating research data in an experiment, some information surrounding the experiment is also worth keeping separate records of, in a lab notebook. The notebook is your designated space for recording notes and comments on the protocol. In addition to being kept well-organised and accurate, a lab notebook can include the following:

- Relevant details on what you did in the lab, when, and how

- Your name and affiliation

- What project is the experiment part of

- Information on lot and batch numbers for used consumables (e.g. reagents and chemicals)

- Information on what metadata is collected for each data type collected

- What happened and what did not happen

- How the result was treated and analysed

- Your interpretation of the outcome and how you plan to proceed

Exercise 3 - Test yourself on record-keeping statements

Read the following statements and decide which ones are true (T) or false (F)

- Analogue and digital records make information equally findable.

- New information in digital records can be easily shared with other users.

- Analogue records can be kept safe from any physical accidents.

- All researchers in a shared lab should have access to the same platform for keeping records and taking notes.

- Digital records should follow the same backup strategy as the data they describe.

Solution

- Analogue and digital records make information equally findable. (F)

- New information in digital records can be easily shared with other users (T)

- Analogue records can be kept safe from any physical accidents (F)

- All researchers in a shared lab should have access to the same platform for keeping records and taking notes (T)

- Digital records should follow the same backup strategy as the data they describe (T)

To better understand these statements in practice, it is useful to compare key characteristics of analogue and digital records side by side.

Analogue vs. Digital Records – A Practical Comparison

| Aspect | Analogue | Digital |

|---|---|---|

| Findability | Low–medium | High |

| Shareability | Low | High |

| Backup | Weak | Strong |

| Long-term preservation | Vulnerable to physical damage | Vulnerable to format/software changes |

| Legal admissibility | Often strong | Depends on integrity controls |

Digital records reduce many risks but introduce new ones, such as file format obsolescence, software dependency, and access control.

Backing up your files and folders

Even if memory serves you well, technology might not. Know your storage needs and plan solutions accordingly. Factors that play a role include data sensitivity, ease of access, file size, and overall data volume. You can also ask yourself where, how and by whom your data will be produced, accessed, transformed, and transferred throughout and beyond the project.

- Nearly all data, metadata and project information necessary to understand your analysis and results require some sort of backup strategy.

- Try to keep backup in three separate locations, on at least two different kinds of media (server, portable hard drive, cloud). Consider off-site backups.

- Never back up your data on portable drives only (SSD or ATA), and particularly not on USB sticks!

- Robust backups need to be automated.

Exercise 4

Discuss in pairs the validity of the following statements on data backup:

A. I have my most important data backed up on my laptop. I have never experienced a hard drive failure, and my current laptop has a brand-new state-of-the-art hard drive. Therefore, I don’t need external backups.

B. All my data is stored in a cloud service or a computation cluster (e.g. UPPMAX).

C. My data is on a portable hard drive. There is a backup of the most important files on a shared USB stick in my research group.

D. My data is on a departmental backup administered by my University. Additionally, we have a server for all the data stored in our project.

E. We have no shared backup at all. All members of our research group are responsible for their own data.

Comments

A. Unsafe and not recommended. All hard drives are susceptible to failure. In case of failure, all data will be lost.

B. Cloud services can be sufficient as a backup, but are not fail-safe. It can be sufficient in combination with a secondary backup, such as on a shared server. For certain types of data (e.g. sensitive information), a cloud service may be outright inappropriate.

C. Not a good solution. Both portable hard drives as well as USB sticks are prone to failure.

D. A good solution in general. Data is stored independently in two separate systems. Centrally administered services are usually organised in such a way that partial failures do not affect the users.

E. Worst possible alternative. A disaster waiting to happen.

Creating a backup strategy in 10 steps

- Find out whether your institution has a backup strategy

- Determine what you want to back up

- Decide how many backups you will need and how frequently to back up

- Decide where backups will be stored

- Determine how much storage capacity will be needed

- Determine if there are tools you could use to automate backup

- Determine how long backups will be kept and how they will be destroyed

- Determine how personal data will be protected

- Devise a disaster recovery plan

- Assign responsibilities

Further reading